Anecdotes and Perspectives

by Eliot Goldman, an American Now Residing Abroad

Have you wondered what it would be like to live and work in Paris?

I know I’ve been curious! I have a friend living there, who can provide insights on how life there differs from life in the United States.

Eliot Goldman is my old friend and colleague dating back to our years spent working at DEC. Eventually, I started a new path as an independent Human Resources consultant, and Eliot relocated to begin a new life and career in Paris.

I’m excited to be able to share Eliot’s reflections and experience in the form of enjoyable, informative anecdotes he’s creating for readers of Friends of Rosanna M Nadeau, a Facebook webpage. Readers will find these anecdotes listed in the order in which Eliot wrote them for us, most recent story first.

We look forward to comments and questions! Eliot will enjoy responding and engaging in discussions.

With many thanks and great appreciation, let us begin. Thank you, Eliot!

Let The Stories Begin!

Final Blog Post: April 20, 2025

Hello, All,

The PARIS column by Eliot Goldman is being retired! We thank Eliot for all of his wonderful stories and insights about life in Paris and wish him well!

I’ve greatly enjoyed Eliot’s perspective and lessons tucked into informative, engaging writings that so often stirred the imagination and brought so much value to our page.

Please join with me in wishing him a fond farewell and all the best in his retirement.

Blog Post: April 16, 2025

Sundays in Paris remind me of what Sundays used to be when I was growing up in Massachusetts when we still had the “Blue laws.” In France, aside from shops that sell food and wine and drug stores, most businesses are closed. But food shopping here is different as well. We still have grocery stores, but we also have butcher shops, fish markets, bread bakeries, pastry shops, cheese shops, fruit and vegetable stores, and chocolate shops.

Shopping malls with chain stores are a recent addition to local commerce, and in Paris, a lot of them are in renovated train stations. As a result, Sunday is not a day for hanging out at the mall. There are other things to do.

A Parisian Sunday is divided into three distinct and quite different moments/Sunday morning, Sunday early afternoon, and Sunday late afternoon.

In some sections of Paris, Sunday morning is also market day, and the sight of all the stalls displaying all their foodstuffs is itself a feast for the eye. I live near the rue de Lévis, which is a permanent market street as it is lined on both sides with a series of shops and stalls. Food shopping on the rue de Lévis on a Sunday morning, particularly when the weather is nice, is really special: the street seems to take on a life of its own. People will be far more numerous than usual – of course – but this is rare enough to be pointed out – they will be walking at a leisurely pace.

Weather permitting, cafés will set up tables and chairs, all of them taken up by Parisians sipping cups of espresso or glasses of beer depending on the season. Street musicians are serenading you with varying degrees of talent. Men and women are selling bunches of flowers in the street: now, it’s daffodils – a sure sign that spring is on the way.

But it is inside and around the food shops that Sunday morning is truly celebrated. In the rue de Lévis, there are at least five boulangerie-patisserie, each of them baking and selling bread and pastry. One of them is certainly better than the others, as can be easily guessed by the long line of patrons waiting patiently on the sidewalk. A pastry for dessert for Sunday dinner is almost an institution in France, and so anyone leaving the shop will be carrying a loaf of bread (most often a baguette) in one hand and in the other, the very familiar and very precious square white box containing the pastry.

Walking past the windows or stalls of caterers is also enough to make you put on weight just by inhaling the fumes or by looking at the gorgeous display – reminiscent of a still life by a Flemish painter – composed of patés, croustades, stuffed seashells, roasted chickens, roasted suckling pigs, eggs in aspic and festoons of sausages.

The second part of the day begins at about 2 PM, when people have eaten the last crumb of pastry, licked their plates clean, and sipped the last drop of espresso from their cups. Then they leave home, in families, couples, groups, or alone to pour out along the banks of the Seine, the Quartier Latin, around Notre Dame, into the Jardins de Luxembourg or the Tuileries or line up for films of the major museums of the capitol or simply sit at a café terrace in order to indulge in that most Parisian activity: watching people, while having a drink.

Now, Notre Dame, les Tuileries, and the major museums are usually mobbed with tourists as they are mentioned in every single guidebook. So, they are not representative of how Parisians spend an early Sunday afternoon. The banks of the Seine (les quais) are not rated as major landmarks, and on a Sunday afternoon they are a favorite hangout for a large part of the Parisian population and provide a precious atmosphere of safety, gentleness, and family life.

They are also closed to traffic, giving hikers, joggers, and cyclists a field day for practicing their favorite sports. As cars and motorcycles are banned, young couples stroll along with their toddlers. Families with kids ranging in age from four to ten or twelve years of age will go cycling quietly, or if more athletic, will go roller skating. In the midst of all that din, you will have the refreshing site of young lovers walking hand in hand and then coming to an unexpected stop for a passionate hug or an even more passionate kiss, and sometimes as if life wanted to give us a brief but powerful metaphoric insight, you will see an elderly couple sedately walking arm in arm just a few yards ahead of their former and younger selves.

And so, without even noticing it, you reach the fateful moment of late afternoon, when suddenly people realize they have to go back home, and there will be traffic snarls everywhere, and the Métro and buses will be overcrowded. Suddenly, the charm is broken; the ceasefire has ended; faces become surly; eyes start glaring, and you can feel the atmosphere becoming as tense as the bodies. But Monday through Friday will soon pass, and before you know it, it will be Sunday again – Bon Dimanche (Happy Sunday).

Blog Post: April 9, 2025

Social scientists have labeled some of the major changes in our lives as transitions. Loosely defined, a transition is a major change in life that begins with an ending and ends with a beginning. On a personal level, things like marriages / divorces, promotions at work / losing a job, death of a loved one / birth of a child are transitions. It’s fair to say that transitions are personal, but that we are not the first people to have this happen. There are almost always advice books and different types of therapists to help us cope with the change and create a new beginning.

Then there are also the times of sudden global change when we’re no longer sure of everything we thought we knew, and there are no therapists. In my life, three moments stand out: that assassination of President Kennedy, the World Trade Center and Pentagon terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001, and the first months of President Trump’s second term of office. For me, all of these have been times that I wish hadn’t happened, and when there was no available advice on what individuals might do to make things better. A significant difference for me was that I was a college sophomore in the US when President Kennedy was assassinated, but living in France for the September 11th terrorist attacks, and the beginning of the second Trump term of office.

I remember what occurred in France on September 11th and the days that followed. The terrorist attacks were the only story in the news that day. The government ordered all French flags flying on public buildings nationwide to be lowered to half-staff until the following Friday in sympathy and solidarity. There was the same sense of sympathy and solidarity among the French as there was among Americans. When the attacks took place, it was the middle of the afternoon in France. When the news became widespread, a steady stream of French colleagues came into my office to see if I knew, if I was alright, if I had family or friends living or working in the areas attacked, but mostly they came just to express their feelings of horror and sympathy. As I was one of the few Americans working there, at that time, I represented America to them, and they felt that by sharing what they felt with me, it would be like sending a card or flowers to the USA. Many members of my wife’s family called to make sure that none of the members of my US family were victims.

The reactions to the attacks on the US showed once again how important the US is to non-Americans. For people of good will and for people of unspeakably evil intent, America has been a symbol and a certainty: for the last 80 years, one of the stable elements in a changing world. I’m not sure most Americans understand just how much of a symbol we are and what it means to the rest of the world, when the US does the unexpected.

But there’s another important difference. Yes, French colleagues came to me to express their feelings about September 11th. I represented America to them. The French had an entirely different reaction to President Trump’s starting a trade war. To say that the French are unhappy about Trump’s tariff policies doesn’t match the intensity of their emotion. In my conversations with them, they are angry with the US government, but not with the American people. Compare that with the war against Iraq when the French refused to join the US coalition, and the US government referred to them as “Cheese-eating surrender monkeys,’ and relabeled French fries, freedom fries. This difference, separating judgment of a people from judgment of a government elected by the people, was something new for me. Maybe, we should adopt it in the US.

I have found that one of the best ways to learn about your own country is to live somewhere else just because you become aware of differences. Whenever you notice a different way of doing something, you think, ‘That’s different: I wonder why they do it that way and not the way we do it back home.’ If you’re curious, you can find out, which leads you to think that either they’d be better off doing things the US way or the US would be better off doing things in the same way as where you’re visiting. Either way, you’ve learned something new and maybe have a deeper understanding of your own country.

Blog Post: April 2, 2025

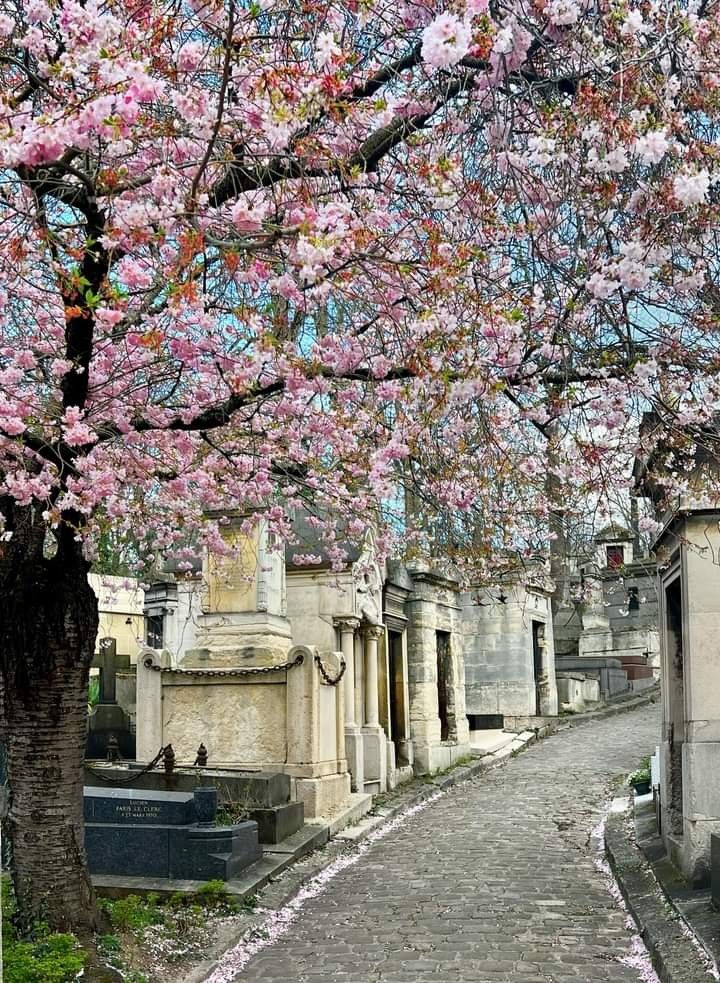

Père Lachaise cemetery

In a recent article, I described the differences between English or American parks and French parks: how the English try to imitate a natural setting in a cityscape and the French try to use natural elements such as trees, flowers, and grass to show that humans can make better designs with these elements than Nature itself.

The other day, while walking through a large Paris cemetery, it struck me that the difference in park design carries over to cemetery design. Unlike American graveyards, French cemeteries are characterized by architectural extravagance and abundant vegetation. The former is probably due to aristocratic influences and the reaction of Catholic countries to the Protestant reformation; the latter from an imperial idea – the garden cemetery. But the different approaches raise the question of how we memorialize and honor the dead.

As a result of the design and landscaping, Parisian cemeteries have become tourist attractions. I’ve lived in several places in the US, but I don’t remember any of the cemeteries as places where tourists would want to visit. OK, there’s the Granary Burial Ground on Boston’s Freedom Trail.

Let’s take one Parisian example, the largest Parisian cemetery: Père (Father) Lachaise. Père Lachaise was Louis XIV’s confessor. He had lived on the property but was not buried there. Some of the more famous people buried there are Chopin (except for his heart, which is buried separately in Poland), Molière, Edith Piaf, Rossini, Simone Signoret, Yves Montand, Gertrude Stein, Alice B. Toklas, Oscar Wilde, Isadora Duncan, Maria Callas, and Jim Morrison.

The Père Lachaise cemetery was created by Napoleon I in 1804 because the capital was badly in need of more space to bury its dead. The best place seemed to be a plot of land belonging to the Jesuits. The government purchased it at a low price as at the time it was outside the city limits of Paris.

Napoleon immediately decided to turn the future cemetery into a modern, pleasant and beautiful space not only to add to his own prestige, but to entice the reluctant Parisians into burying their dead in such a remote place far from any church and the graves of departed worthies. The best way was to make Père Lachaise fashionable, so the coffins of certain celebrities were transported to the new graveyard from their existing burial sites. Small but flamboyant chapels were built to accommodate some ducal or princely bones.

The cemetery is as large as the Vatican City. Jim Morrison’s grave is still the most frequently visited, mostly by crowds of teenagers. Because of its abundant vegetation and high elevation, the cemetery is one of the least polluted areas of Paris. Above all, the architectural extravagance and the elaborate decorations of the chapels, monuments, and tombstones provide tourists with a treasure trove for thematic visits.

Given its size and given human nature (in France, anyway), it is also a site for what might be called dark humor. One example of this was Oscar Wilde’s memorial. Oscar Wilde died in Paris. Apparently, his last words were, “This wallpaper and I are fighting a duel to the death. Either it goes, or I do.” He was too poor to pay for a tombstone, so his friends and admirers commissioned one for his grave. The sculpture is a male sphinx. Although Wilde was gay, he had lots of female admirers who showed their devotion to him by kissing the statue’s genitals, smearing their lipstick. This reached a point where lipstick was attacking the stone, so the city government covered one side of the tomb in plexiglass. Not everyone was pleased with the visible genitals and one day someone took a hammer and chisel and castrated the sculpture. The guard on duty, seeing the result, had to report the incident to the cemetery administration. Now in the official log, you can see the following report: “Oscar Wilde memorial: testicles removed by unknown person.”

A second example is the tomb of Victor Noir, who was murdered by a nephew of Napoleon III in the 19th century. For reasons no one has explained, the sculptor created a statue of Victor lying down with an obvious bulge in the crotch. And for other reasons that defy logic, visiting the tomb became popular for couples having difficulty conceiving children. The tradition developed that the woman would go there and rub the crotch while kissing the lips. There are no records about how many children were born as a result, but both the statue’s lips and crotch show the effects.

Cemeteries provide lessons about how we treat people when they’re dead. I wish we had more that shows us how to treat one another while we’re alive.

Blog Post: March 26, 2025

One of the experiences you find in adjusting to life in a foreign country is discovering that something that appears to be familiar isn’t.

Take popular songs for example. I assume that most of you have heard and know some of the words to the song, “My Way,” made famous by Frank Sinatra. The English lyrics were written by Paul Anka, although I’ve never heard a recording of him singing it. The song tells the story of someone nearing the end of their life and being proud of having overcome life’s obstacles: “But through it all, I stood tall and did it my way.”

So, if you were in France and heard someone singing what sounds like the same melody but in French, you might think that they translated, “My Way,” but you’d be wrong. You’d most likely be listening to Claude François singing, “Comme d’habitude,” translation “As usual.” Paul Anka heard this song, thought it had a great melody, but the lyrics, even translated, wouldn’t appeal to an American audience. So, he kept the melody but composed a different song. Here’s the first verse in French and translated into English:

| Je me lève Et Je te bouscule Tu ne te réveilles pas Comme d’habitude Sur toi je remonte le drap J’ai peur que tu aies froid Comme d’habitude Ma main caresse tes cheveux Presque malgré moi Comme d’habitude Mais toi tu me tournes le dos Comme d’habitude | I wake up And I nudge you You don’t wake up As usual I pull the sheet up over you I’m afraid that you are cold As usual My hand caresses your hair Almost in spite of myself As usual But you turn your back to me As usual |

“My Way,” is a song about someone nearing the end of life, proud of what they were able to do. “Comme d’habitude,” is a song about love dying.

Another example is the song, “Autumn Leaves,” sung by many American singers, but primarily made famous by Nat King Cole. Before it became a hit in English, it was a French song, “Les Feuilles Mortes,” (“Dead Leaves,”) sung most famously by Yves Montand. Both songs are about the end of a romantic relationship, but I find the French song a lot more morose. Here are some of the key verses from both songs:

Autumn Leaves:

The falling leaves drift by the window

The autumn leaves of red and gold

I see your lips, the summer kisses

The sun-burned hands I used to hold

Since you went away the days grow long

And soon I’ll hear old winter’s song

But I miss you most of all my darling

When autumn leaves start to fall

Les Feuilles Mortes

| Les feuilles mortes se ramassent à la pelle Les souvenirs et les regrets aussi Et le vent du Nord les emporte Dans la nuit froide de l’oubli Tu vois, je n’ai pas oublié La chanson que tu me chantais C’est une chanson qui nous ressemble Toi tu m’aimais, et je t’aimais Nous vivions tous les deux ensemble Toi qui m’aimais, moi qui t’aimais Mais la vie sépare ceux qui s’aiment Tout doucement, sans faire de bruit Et la mer efface sur le sable Les pas des amants désunis | The dead leaves collect by the shovelful The memories and regrets as well And the North Wind takes them away Into the cold night of forgetting You see, I haven’t forgotten The song that you sang to me It’s a song that resembles us You, you loved me, and I loved you We lived together You who loved me, me who loved you But life separates those who love Softly, without making a sound And the sea erases from the sand The footprints of separated lovers |

Rather than being frustrated at not knowing, think of it as learning one more thing as you adjust to your new environment. Or as Leonard Cohen put it in “Anthem,”: “Forget your perfect offering. There is a crack, a crack in everything. That’s how the light gets in.”

Blog Post: March 19, 2025

Here’s a question that I imagine hasn’t occurred to most of us. Why do cities have parks?

If you study parks, all of which are man-made in the US or in England, it occurs to you that the town planners wanted to recreate a natural landscape in the middle of an urban setting. If you study parks in Paris, you realize the planners (or somebody) had something else in mind. The US and English idea seems to be that recreating natural settings in a city is somehow beneficial to the city residents.

Carrying that idea to its utter limit makes one think of Henry David Thoreau who left his home in Concord Center to live at Walden Pond. Most Parisian parks are fairly old and date back to the 17th or even the 16th centuries when they were built as private gardens for the royalty and nobility. The idea was not to recreate a natural landscape, but to take natural elements such as trees, shrubs, and ponds, and use them as elements to design something more beautiful than a natural landscape. There were parks created in the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries, but they were created for the public, and always based on a government plan, whether France was a kingdom, an empire, or a republic.

As a consequence, almost all the parks, no matter how different they are in terms of size or design, share some common characteristics. The first striking element is that they are all fenced-in (sometimes by beautiful iron railings) and closed from sunset to 8 or 9 in the morning by gates that can be truly impressive; e.g., le Jardin du Luxembourg. A second feature is that all the parks designed before the second half of the eighteenth century follow the pattern of ‘Jardin à la Française’ brought to its perfection by LeNôtre – King Louis XIV’s official gardener. The purpose of a Jardin à la Française is to glorify the sway of the king or noble over nature and chaos and show off his wealth and power.

A Jardin à la Française is remarkable for the magnificent vista produced by a long alléé (alley) starting at each entrance, lined with trees of exactly the same size, shape, height, and species. The space between the trees is the same except when the space is taken by the statue of a mythological hero. At least three large artificial ponds will divide an alley at regular intervals. Each pond is surrounded by sculptures of mythological characters. At the center of the middle and largest pond will be a fountain with a sculpted creature spraying water into the sky.

This is typical of LeNôtre’s idea of a royal garden. The concept originated at Versailles and then spread to Paris (le Jardin du Luxembourg) and other places around the capital where members of the royal family or aristocracy lived.

Well into the 18th century, royal or princely gardens had a symbolic as well as social value and function. Being admitted as a guest was of the utmost importance for one’s social status. They served as stages where their owners flaunted their wealth and prestige, and where visitors, in turn, took on some of the glory and magnificence and increased their own feelings of self-importance. Even when a garden was open to the public, as was the case with le Jardin du Luxembourg in 1642 thanks to the generosity of its owner, Gaston d’Orléans (King Louis XIII’s younger brother), it remained a place where you watched and were watched. After its opening to the public, residents of the neighborhood (bourgeois, clergy, writers, and nursemaids) would rent chairs and sit down in the shade to observe and discuss “le beau monde,” aristocrats of both genders, as they engaged in showing off, pretending and performing.

Nowadays, le Jardin du Luxembourg is mainly an oasis of beauty and quiet in the middle of Paris. It is also a very convivial place. Lovers appreciate its benches for hugging and kissing. Single people use chairs: usually two per person, one for the bottom and one for the feet. Aside from sitting there, the occupants might be reading, watching the scenery, or feeding pigeons. Feeding pigeons is strictly prohibited and subject to a fine, but this is France, the country where prohibited actions are more enjoyable. There is also a small restaurant where inefficient waiters serve indifferent food and where chairs, when put outdoors during fine weather, have a dangerous propensity to fall over.

Kings, emperors, and aristocrats continued creating parks in Paris long after the 17th century, but from the late 18th to the beginning of the 20th, the rigor and harmony of le Jardin à la Française were superseded by romantic aspirations and fashion: symmetry and prospects were replaced by fake ruins, small grottoes, bowers, and bridges. Le Parc Monceau, created by the Duc de Chartres in 1744, is typical of the later trend. This same romantic and mysterious atmosphere can be found in Le Parc des Buttes Chaumont (opened in 1867) and Le Parc Montsouris (1870). Le Parc des Buttes Chaumont is one of the few Parisian parks to have hills. Before it was a park, it was a gypsum quarry, and the site of the gallows before the invention of the guillotine. Nowadays, families with toddlers and young kids stroll peacefully along meandering lanes while enjoying the beautiful view over Paris from the top of the butte.

We Parisians love our parks. If you’re planning to visit, add some parks to your itinerary. They are one of the places where you will see more Parisians than tourists.

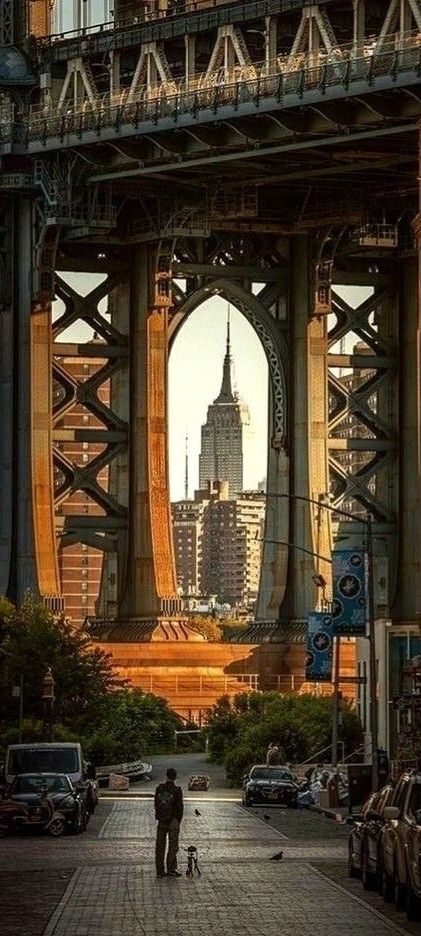

Blog Post: March 12, 2025

Image Source: Pinterest

As we Parisians live in one of the world’s most crowded cities, we learn how to adjust to living in small spaces and making do without our own cars. One of the things we do differently is food shopping. We do it pretty much every day because we don’t have space in our apartments for large freezers and whatever we buy when we go shopping, we have to carry home because we don’t have cars. If you’re asking how can I live like that, I have two replies. First, I prefer it and second, if my grandmother could do it, so can I. One of the things you would notice in any residential neighborhood is the number of specialized, small food shops. We still have bakeries (boulangeries, pâtisseries), butcher shops (boucheries), cheese shops (fromageries), greengrocers (fruits et légumes), chocolate shops (chocolateries, confiseries), and fish shops (poissonneries).

The shops are not self-service, so what happens inside the shop differs even more from the usual American food shopping experience. Let’s take buying fish as an example. In an American supermarket, you generally buy fish at a fish counter or pre-packaged in a refrigerated case. The person who sells us the fish weighs and wraps the steaks or filets. The steaks and filets are as distant from the animal that provided them as a steak is distant from a cow. For meat, poultry, and fish, we like to separate our food from the animal. We have different words for the animal and the food: for example, cow and beef. I have more than once heard someone say, ” I like eating fish. I just don’t want it staring back at me from the plate.” A typical New England fish market or fish counter at a supermarket has haddock, cod, flounder, trout, salmon, lobster, clams,scallops, oysters, shrimp, and swordfish. When you view them in the case, they look more like the food you’re going to eat than the animal they once were.

I don’t know the English words for all the fish and shellfish I see in French fish markets.I do know that in addition to a everything you can find in a New England market, you also find octopus, squid, sea urchins, snails, sea bream, monkfish, red mullet, gray mullet, rockfish, and eels, plus lots of fish that I only know the French for because I can’t find the translation in my French-English dictionary. For instance, I know what Sandre looks like and tastes like, but I don’t know the English word for it.

When you enter a French fish market, you see fish – fish the animal, not fish the food. There’s typically a display of shellfish: all still in their shells. By buying and eating scallops still in their shells here, I learned that the scallops I ate in New England were minus one of the tastiest parts of the animal – the roe. Then there are the fish, not packaged or behind glass, but laid out on crushed ice, mostly whole fish except in cases like tuna, where the whole fish would be too large to fit in the shop. You don’t know exactly when the fish were caught, but you can do what people have been doing for ages to judge the freshness. You can look at the eyes and the gills and you can smell how fishy the fish smells.

There’s a division of labor in the shop: the salesperson, the cleaners, and the cashier. The salesperson (le marchand du poisson) is like the orchestra leader. You can go to the salesperson and say, “I’m serving a total of six people for dinner and I plan to serve a particular wine with the fish course, and these are the other dishes I’m planning to serve before and after. What do you recommend?” And the marchand du poisson will make a recommendation. He or she will tell you how much to buy and how to prepare it. I’ve noticed that French homes have fewer cookbooks than American homes. One reason might be that the living space is so small that there isn’t room for them. But another reason is that all the different food merchants know how to cook everything they sell. So you don’t just go to buy fish, you also go to get advice on what to do with it. If you’ve ever seen a monkfish or a ray, you’d know why that’s important because looking at them doesn’t really give you a clue as to how to prepare them. Generally, you’re not the only person in the fish market. There are other customers as well as other employees. And, how you prepare your fish is a fit subject for a community discussion. Everyone has their opinion about which herbs to use, whether to cook it with wine, whether to grill, fry or roast it and for how long. It’s considered perfectly appropriate for strangers to butt into your conversation with the marchand du poisson to give their own ideas about the fish you’re preparing. These same strangers will avoid eye contact with you outside the shop because that’s the way life is in this city.

Hopefully, you’re not in a hurry because nearly everyone in the line goes through the same ritual. So by the time the marchand has reached you, you’ve already collected several recipes. The other day, I purchased a sea bass that I wanted to roast. The marchand suggested that the perfect seasoning would be dried wild fennel. He then went to the rear of the shop, found some dried wild fennel and put it into the bag along with the fish. But at this moment, you’ve agreed to buy a fish that still needs to be paid for and prepared for cooking. The marchand delivers the fish to a cleaner who scales and guts it or scales, guts, and filets it. They do not remove the head because here everyone knows, because their mothers told them so, that the only way to prepare tasty fish is with the head attached. The marchand then gives you a ticket with the amount you owe which you tbring to the cashier. You pay the cashier for your fish, tip the fish cleaners, say au revoir to everyone and head home.

So what have you done? Obviously, you’ve bought a fish or a piece of fish. But beyond that you’ve engaged in conversation with complete strangers in a city where people avoid making eye contact as they pass one another every day. Depending on where we live, we weave the fabric of community in different ways and in different settings.

March 5, 2025

When you move to a foreign country, you learn very quickly that it’s important to know the local language. You probably knew that before moving, but once you’re there you also find that there are some words from your first language that don’t translate comfortably (or at all) into your second language because the item doesn’t exist. One crazy example is for types of beef steak. The T-bone (or Porterhouse) steak doesn’t exist in France because meat is cut up differently. So if you looked up T-bone in an English- French dictionary, either it wouldn’t be there or there would be a description, but no one word translation.

Another word I came across recently that I wanted to look up in an English dictionary is the word flâneur. I first came across the word in a book in French about interesting walks in Paris. Paris is a city best explored on foot, and a flâneur is someone who wanders in an area without a preset plan, going in one direction or another depending on what looks interesting. The French-English dictionary had a one word translation, which to my judgement, was an error. They translated flâneur as loafer or idler. No: the flâneur is exploring the locale because they want to explore the locale.

Paris is a city that invites you to explore it. Not all cities do that or do it as well. Boston has the Freedom Trail, which gives your walk a purpose – a history lesson. For me, the deeper issue here is about whether it’s OK to enjoy yourself. Boston tells you to have a purpose beyond pleasure; Paris tells you to enjoy and to want to learn more by enjoying!

There are other things here that make it easy for you to explore and enjoy the city. Here’s one: public toilets. I haven’t been to Boston for a while so I don’t know if they now have public toilets. When I left, they didn’t. I had to know which hotel lobbies and department stores had facilities available because there weren’t a lot of other choices. Thinking about the lack of public toilets in Boston makes me wonder if the Puritans who founded the city decreed that there should be no public toilets because their presence would make people think about “that part of the body,” and that might lead the otherwise virtuous away from paths of righteousness. Or perhaps they thought that people should be in the city only to go about their business, but not to enjoy themselves because that was a form of idleness and once again temptation would rear its ugly head. It must have something to do with the Puritan influence because in the US, we don’t even call them toilets. We call them restrooms, but who goes there to rest?

In Paris, we have les toilettes (not restrooms) conveniently located throughout the city. They are self contained, self-cleaning units. When one is vacant and not cleaning itself, you press a button and the door slides open. You enter and answer nature’s call, and there’s even a sink to wash your hands. As soon as you leave the door closes and locks behind you, the interior of the entire unit is washed with a solution of scalding water and bleach, and then dried with hot air. At locations where there are likely to be crowds, such as Notre Dame cathedral, you usually find underground public toilets. These are also very clean in spite of all their use because they are kept clean by “les dames pipi.” When you enter, you leave a tip for les dames as a way of saying thank you and to avoid being the target of a nasty remark by one of the dames. One of the things that I’ve had to get used to was having a dame pipi cleaning the urinal next to the one I was using while trying to maintain a look of complete nonchalance. It’s possible if you develop the Parisian habit of not making eye contact or beginning a conversation with a total stranger.

And here’s another way we ask people to prolong their time in the city. Paris has public benches along the sidewalks. There are benches in the shade along the sidewalks along most of the city’s major avenues and in the parks. When the weather is nice, the benches are usually full. People sit and talk to each other. Young (and not so young) couples embrace. Others sit and drink water or their beverage of choice – drinking alcoholic beverages in public is legal in France.

And you: Do you live in a place that lets you know they want to enjoy your visit and stay as long as you want?

Blog Post: February 27, 2025

Although I’ve lived here for twenty-five years, there are neighborhoods in Paris that I’ve never explored. As I enjoy walking and need to exercise, I’ve started going for walks in neighborhoods I don’t know. Yesterday, during my walk, I discovered an old public bath.

The public bath is not new; the Romans had them and built them in the lands that they conquered and colonized. You can see the ruins of one in the Latin Quarter. Older American cities used to have them, but they seem to have mostly disappeared from the American urban landscape. Nowadays in Boston, the only public baths are at public swimming pools because you’re required to shower before entering the pool. There are still private steam baths or saunas that you can frequently find in immigrant neighborhoods, particularly East European and Finnish. Paris still has 16 public baths (Bains Douches) and each has about 90,000 visits a year.

They are not scattered evenly around the city; nine of the sixteen are found in the 18th, 19th, and 20th arrondissements in the northeast corner of the city — the poorer neighborhoods. Historically, these have been the poorer neighborhoods for more than a hundred years, regardless of changes in the local population. How did that happen? Much of Paris was torn down and rebuilt in the second half of the 19th century during the Second Empire. That’s why when you visit, you notice the architectural harmony. The person responsible for tearing down and rebuilding the city was Eugene Haussmann, who was the Prefet of Paris during the reign of Louis Napoleon Bonaparte (Napoleon I’s nephew) who decided that being the elected president of the second French republic wasn’t quite what he wanted so he staged a coup d’etat against himself and then had himself declared Emperor Napoleon III. The Prefet is the highest government official in a region, comparable to an American governor, but he is appointed by the president rather than being elected by the people. Before Haussmann rebuilt the city, it was a series of neighborhoods with narrow streets with open sewers running down the middle. Haussmann said that he decided to undertake the work in reaction to a cholera outbreak. It may also have been in reaction to the massive uprising in 1848, because the layout of Paris streets had made it impossible to quickly move troops from one neighborhood to another to quash the rebellion.

Haussmann’s original plan resulted in many of the poor being forced out of the city center and moving to the northeast of the city or being forced out of the city altogether and into the suburbs because they could no longer afford the rents. It was not, however, his intention to force the poor out of the city. As the Prefet, his office had authority over building plans for every building in the city, which is why when you look down a boulevard in Paris, all the buildings are the same height all the way to the horizon. When a single family occupied a six-floor building, the family was to live on the lower floors and the servants in rooms under the roof. In an apartment building, the wealthy would live in apartments on the lower floors, and the poor in individual rooms on the top floor. On the top floor, there was a common toilet in the hall but no bath or shower. In fact, this situation continued into the early 1970’s when a majority of Paris apartments still didn’t have bathrooms.

For the poor, and in fact for most Parisians, the only shower available was at the public bath. There were public baths before the mid-19th century, but they were meant for the well-to-do and were considered a luxury. At the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries, the city undertook a public hygiene campaign including building public baths. In addition to public baths, the government also built communal kitchens because the small apartments that usually lacked bathrooms, also lacked kitchens. Many of the public baths built at that time had their external tile work added in the 1920s in the Art Deco style and are now classified as historic monuments. That’s no big deal in Paris; almost every building in the city is classified as an historic monument. At the time most customers of public baths were large families and elderly men and women with small pensions who couldn’t afford apartments with bathrooms. At the public bath, showers were free, but you had to pay a few francs to use a bathtub.

The Paris population has changed since then. There are not many large families living in Paris. Many of those that do live in public housing, which is more likely to be in a nearby suburb, where apartments have bathrooms. There are fewer one room apartments because beginning in the 70’s, developers would buy several adjoining one room apartments and convert them into larger apartments including the addition of kitchens and bathrooms. As elevators were added to buildings at about the same time, top floor apartments became more desirable and more expensive. The public baths now primarily serve the homeless; mostly men. They are kept spotlessly clean, and are open five and a half days a week. The shower is free but soap and towels are not provided. They no longer have bathtubs. Each client is limited to 20 minutes so that the wait does not become too long for the other clients in line and to prevent clients from washing their laundry in addition to showering.

The city is still interested in promoting public hygiene and in doing what it can to provide some measure of dignity to the homeless. In one of the most densely populated cities in the world, concerns about public hygiene are necessary. But I also find it commendable that in an increasingly indifferent world, the French care about the dignity of the least among us.

Blog Post: February 21, 2025

Montreal – Image Source: Pinterest

Every country has its symbols that represent the nation, its people, and the government. In the United States, we have the bald eagle, the Statue of Liberty, and Uncle Sam. When cartoonists want to represent the federal government as a character, it’s usually Uncle Sam. The French have the rooster (le coq sportif) and la Marianne. Just like Uncle Sam, she was not a real person. Uncle Sam represents the US government. La Marianne represents the French Republic. She represents the republic because in its earlier history, France was a monarchy. In fact, there are still people in France who think the country should be a monarchy again and there’s even a Count of Paris ready to assume the throne should that ever happen. You see la Marianne on French stamps, and there’s a bust of her in every city hall in the country.

Like Uncle Sam, la Marianne was first represented in works of art. There’s the famous painting by Delacroix, “The 28th of July: Liberty Leading the People,” which shows a woman holding the French flag in one hand, a rifle in the other, and leading a charge over a group of fallen fighters. La Marianne is always shown wearing a red bonnet (the Phrygian bonnet) that became a symbol of the French revolution. In Delacroix’s painting, her blouse has slipped off her shoulders, thus exposing both breasts. In the busts in town halls and on stamps, the artists dressed her more modestly.

Uncle Sam is an artist’s sketch. He has had the same face and clothes from the day he was drawn. La Marianne was that way too until President Giscard d’Estaing decided to honor a French woman by creating la Marianne in her likeness. The clothes stayed the same, but the face changed to become the face of a real person. France being France, it was decided that la Marianne should be modeled to be the likeness of a French actress, and the first actress to have her face be the face of la Marianne was Brigitte Bardot. Yes, in every city hall in France, there was a bust of Brigitte Bardot representing la Marianne. Even a traditionalist like General De Gaulle thought it was an appropriate choice and was heard to have said, “That’s a good choice: after all, her films have brought in more revenue to France than Renault automobiles.”

The US Postal Service has a policy about not honoring people with stamps until they’ve been dead for ten years. They made an exception to this when President Kennedy was assassinated. The USPS probably figures that if any scandal is going to rise to the surface, ten years is time enough for that to happen and by holding off, they can spare themselves and family members of the potential honoree from embarrassment. By using living people, the French government puts itself at risk of having the actress who sat for the sculpture do something that will scandalize everyone and therefore reflect poorly on the people who chose her. But there’s a difference between France and the US here as well. Grounds for scandal in France are not the same as the grounds for scandal in the US. Or, to put it another way: In France, sex is clean and money is dirty; In the US, money is clean and sex is dirty.” As an example, shortly before retiring, former President Mitterrand was asked at a press conference by a reporter from Paris Match if he had been living with a woman who was not his wife, and if the two of them had a child. He answered,”Oui, et alors,” – translation, “Yes, so what.” There was a huge outcry in France: not because of President Mitterrand’s extra-marital affairs, but because a journalist had the nerve to ask him about his private life and the magazine committed the transgression of publishing the article.

The French are no different than Americans when it comes to the government taxing us and spending money. Every French President, when newly elected, has the right of choosing the next Marianne. It’s no longer an actress and that makes it less newsworthy and therefore less likely to create a scandal. I think that the French would have preferred it if President Giscard hadn’t decided to have la Marianne be the likeness of a real person because there are more urgent needs for the government than paying for new sculptures for all the city halls every five years. But whether or not there’s a lesson here, it’s often fun to sit back and observe how small things can lead to great turmoil, provided no one is hurt and particularly, if it’s someone else’s turmoil.

Blog Post: February 13, 2025

I’m an American living in Paris, France, and feel at home in a foreign country. I’ve lived here for twenty-five years, and am still learning how Americans are perceived by the French and other foreigners living here. Starting with the French, most of my contact with other human beings is with French people and part of the conversation when I first meet someone is something like this (translated into English):

Another person talking with me: Ah sir, I notice you speak French with a slight accent. Are you English?

Me: No, I’m American, but I’ve lived here twenty-five years, and have tried to speak French without an accent.

Other person: No, no, please keep your accent. You speak decent French and even we French have different accents. So, you should keep yours. I like it.

The lesson learned here is that the French appreciate when you learn their language and they think that criticizing the accent of someone who speaks decent French is rude.

But not all my friends and acquaintances are French. I have American friends who speak French with an accent that I can hear unlike my own accent. I’ve also met citizens of South American countries and have had the following conversation more than once.

Another person talking with me: What’s your nationality?

Me: I’m American.

Other person: Me too.

Me: From which state?

Other person: Colombia. You Americans seem to forget that people who live in South America are also Americans.

That’s true, but citizens of these other countries have different names for their nationalities such as Colombian, Mexican, Chilean, and so on. We US Americans don’t. I’ve never heard anyone called a “United Statesian.” In Spanish, however, a US American is a “Estadosunidosiene.” The lesson learned here is that we US Americans are not the only Americans.

In addition to South and Central Americans living on their respective continents, we share North America with Canadians plus the French citizens living on the islands of Saint-Pierre and Miquelon. But let’s leave aside for the moment those brave 5,000 souls living on those two islands. When I was young and traveling through Europe in the 70’s, it was easy to identify Canadians because so many of them had sewn a Canadian flag patch onto their backpacks. One night in a bar with nothing better to do, I struck up a conversation with the person sitting next to me and asked him why so many Canadians had the flag patch on their backpack. He replied, “It’s so people don’t think we’re American.” Many years later, a Canadian colleague once told me that Canadians were as un-American as it’s possible to be under the circumstances.

So, two very different situations: one in which someone whom I didn’t think of as being American told me that she was, and the other in which someone made it a point to let me know he wasn’t American. Conclusion: it’s impossible to know in advance what you’re going to encounter when meeting people for the first time. How do we then go about fitting in and learning about our new homes? A general rule is to be open to changing what you thought you knew about people, to avoid generalizing, and above all to always observe. And of course, make an effort to learn the national language.

Blog Post: February 7, 2025

Image Source: Eliot Goldman

Anyone who learned a foreign language in high school or college and then never used it in the country where the language was commonly spoken probably remembers grammar rules, verb conjugations, and lots of vocabulary words. What you missed was some of the social rules for using the language, which you would have learned by embarrassing yourself in social situations. In France, for example, before beginning a conversation about something practical, such as buying a bottle of wine, you need to exchange bonjours, (Bonjour= Good day.) But it’s not just bonjour, that you need to say, it’s “Bonjour monsieur, Bonjour madame, or Bonjour mademoiselle,” depending on who’s standing in front of you. If it’s a man, that’s easy, it’s always monsieur. Traditionally, we used madame for married women, and mademoiselle, for unmarried women. That was their definition, and that’s what the words still mean. But there has been a change in how we use madame and mademoiselle without the Academie Française having ruled on its correctness.

There is no French equivalent for Ms. We now use mademoiselle for younger women and madame, for older women without regard for marital status.

Another example is the word, you. In English wedding ceremonies and prayers we still find the second person singular, thou, thee, and thine, but we have replaced it with the plural, you, your, and yours in everyday language. In the US south, there’s still y’all and all y’all, but that doesn’t relate to a social distinction with foreign languages. In French, tu is the singular form of you as a subject pronoun, toi, as an object pronoun, and ton or ta as a possessive. So you might think that in addressing one other person, you would use the tu form. And you’d almost always be wrong. When I studied French in high school, we were taught never to use the tu form because we were told that we would never have to use it. That wasn’t true either. Tu is the form you use with your closest friends, family members, small children, and pets. Using tu with a complete stranger would imply a degree of intimacy that would be considered offensive.

Even after the French revolution and the terror, there are still people belonging to the nobility. Members at that level of the upper class, use the vous (plural form of you) even within families. For anyone else to do it is considered to be putting on airs. An exception to that were General and Madame De Gaulle who used the vous form

As Paris is the capital of France, there are people here from all over the world. Everyone speaks French more or less well as a second language, if not as a first language. But I’ve sometimes found situations where the social rules for using the language change. I’ve made friends with people I’ve met from South America who have wanted me to use the tu form with them even though Spanish has a formal second person singular – su.

One of the great things about living abroad is having the opportunity to learn different ways of doing things. You don’t have to agree with them. You don’t have to adopt them. That’s going to depend on how much you want to fit into the local culture.

Blog Post: January 31, 2025

One of the strange things I noticed moving here was that Parisians had a lot less difficulty knowing my name when they heard it than did people in the Fitchburg- Leominster region of Massachusetts where I lived before I moved here. In the US, when I would say the name “Goldman, “ at, for example, the dry cleaners, the usual response was, “ Sorry, was that Goodman or Goguen?”. Or, “Did you say Elliott Gould?”. In France, there’s a well-known singer, Jean-Jacques Goldman, so whenever I say my name, they frequently reply, “Ah, yes, like the singer. Are you related?” There were 47 other Goldmans in the Paris phone listings, the last time I checked. I’ve never met any of them; however, I would venture to say that the Goldmans in France consider themselves French. You don’t find people with hyphenated nationalities in France. There are no Italian-French, Polish-French, or Irish-French.

A couple years ago, my stepson and one of his friends came to stay with us because they were running in the Paris marathon, and we were the cheapest hotel and restaurant in the city. The friend was of Moroccan origin. Over dinner, he brought up the subject of hyphenated Americans because when he read American newspapers and magazines to improve his English, he kept seeing all these hyphenated nationalities and didn’t understand what that meant. I tried to explain it to him by saying that some Americans were proud to be American but were also proud of their ancestral heritage, and wanted to be known for that as well as for their American nationality. Until I gave him my explanation, he thought it was just a way the media had of labeling people to point out that they were not true Americans, and therefore it was discriminatory.

France, like America, is a land of immigration. There were many different original peoples in the land we now know as France. There have also been conquests and waves of immigrants. When the Romans conquered Gaul, they brought in a lot of Syrians and Greeks from other parts of the Roman empire and settled them in the south of France. Normandy was conquered by Vikings (the Norse men); hence, the name. These same Normans who didn’t think of themselves as French, then went on to defeat the Saxons at the Battle of Hastings in 1066 AD (one of the few dates we all remember if we studied ancient history). There was a massive influx of Russians after the overthrow of the czar, a wave of immigrants from Spain during the Spanish civil war, and so on. Additionally, as former French colonies became independent in the 50’s and 60’s, the French settlers and colonists who had lived there for generations and had as much in common with the European French as we Americans have with the English returned to a country that previously they read about and visited. A lot of the current immigrants are from Africa and Asia.

Americans and others who have never visited France frequently have a picture, almost a caricature, of a Frenchman that we learned from movies. He wears a beret and if he isn’t sitting in a cafe, he’s walking somewhere with a baguette under his arm. Most of the French now think of the beret as an old man’s hat or something worn by a real hayseed with no sense of fashion. The French seem to have replaced the beret with the baseball cap and some of them have picked up the really stupid idea of wearing them backwards. If that weren’t bad enough most of them have a preference for Yankees caps. I always thought the French would make natural Red Sox fans because so few French films have happy endings (which in French is “le happy ending”). Many French who have never visited the US think that average Americans act like the Americans they see on TV shows, which are enormously popular in France. Both the American-held caricature of the French and the French-held caricature of the Americans are wrong.

Some immigrants to France still consider themselves to be whatever nationality they were before they immigrated to France. Some don’t: they consider themselves French. In neither case, do they have two nationalities or a hyphenated nationality. France has never called itself a melting pot, although for reasons both economic and political, it has been and still is a land of immigration. The immigrants are expected to become French without changing the sense of what French is. Immigrants to America are expected to become American and add their own uniqueness to the American character. So, maintaining the cooking analogy, both France and America are countries that immigrants want to immigrate to, so what goes into the pot is the same – immigrants. What comes out of the pot is the same only in that in both cases, new citizens result from immigration. But what happens in the meantime to these immigrants to make them French or American is as different as France is from America.

Blog Post: January 28, 2025

I’m still thinking about the differences between visiting a country as a tourist and moving there, and it occurred to me that in my earlier article, I neglected to mention one of the most important differences: language. As a tourist, no one would expect you to be able to speak the local language fluently. Cities that welcome a lot of tourists try to hire customer-facing staff who speak foreign languages. English is the most common second language that most businesses want their employees to know. It’s a surprising fact that there are more non-native English speakers than native English speakers. So, if you’re an American tourist traveling to the most common tourist spots, you shouldn’t have any difficulty doing everyday things in English. But deciding to live in a place means wanting to fit in, to be well integrated. Being able to speak and understand the national language is part of that.

Trick question: Do all countries have a national language? If by national language, you mean a language identified as the national language in a constitution or law, then the answer is No. The US does not have a national language. English is our most commonly spoken language and immigrants who want to become American citizens need to show proficiency in English to pass the citizenship exam. France has a national language: French. In the First article of the Constitution of the Fifth Republic is the sentence: “La langue de la République est français.” The language of the Republic is French. France even has a government agency responsible for defining the French language – l’Academie Française. The Academy was founded in 1635 by Cardinal Richelieu during the reign of King Louis XIII. Historians believe that his real motive was to give the nobility something to do aside from plotting against the monarchy. The Academy publishes the Dictionary of the Academy, which defines all words that the Academy considers to be correct French, their spelling, and French grammar.The first edition of the Dictionary was published in 1694. They began working on the Ninth edition in 1986 and it was released recently. It’s online, if you’re curious.The Academy spends lots of time deciding which English words are acceptable French; for example, email is not. The correct French word is courriel. Brainstorming is now correct. All official documents, including doctoral theses, must include only words approved by the Academy. Private businesses, however, are free to communicate and advertise in whatever language they want.

Québec, although not a country, has one official language – French – and laws governing the use of English, which is one of two official languages for Canada. All outdoor advertising is French only. Tim Horton’s had to drop the apostrophe from its name. You see apostrophes in outdoor advertising in Paris because some people think apostrophe s (‘s) is how to form plurals. That raises an interesting point for me. If French speakers in Québec use words that are not in the Academy Dictionary, then are they speaking French correctly? Quick answer: Yes, their French is as correct as Parisian French because Parisians use a lot of words that aren’t in the Academy Dictionary, as well. For example, in English we use the word ‘car.’ In France, it’s a ‘voiture,’ and in Québec, it’s a ‘char.. In English, we use the word ‘job.’ In France, it’s an ‘emploi,’ and in Québec, it’s a ‘job.’

If you go somewhere as a tourist, in most cases you’ll have no problems using English. If you plan to move to a foreign country, my advice would be to learn to speak the language as the locals speak it. The locals will be only too happy to correct your mistakes.

Blog Post: January 16, 2025

I was thinking about things that America introduced into France and in addition to Halloween and chewing gum (le chewing (pronounced ‘shoeing’) gum) in France, but la pâte à macher in Quebec) and decided to write about Valentine’s Day.

Living here as long as I have, I’m still amused by American traditions that the French have adopted and modified to make them more French. One of the more fascinating things is Valentine’s Day. It seems strange to have only one day a year set aside for romantic love here in one of the world’s most romantic cities. If the Parisians were any more demonstrative in their display of romantic love in their everyday behavior, they’d be arrested for lewd and lascivious behavior in a public place – in Massachusetts, that is, but certainly not in Paris.

In Paris, couples walking together arm-in-arm will just stop and start kissing. Couples waiting for the Metro or in the Metro carriages will do likewise. Metro stations used to have benches where couples would sit next to each other and embrace. The benches also provided a place for clochards (Parisian winos) to sleep so the transit authority replaced the benches with uncomfortable chairs set far enough apart so that it’s impossible to lie down across them. This proved a real hindrance for the clochards, but loving couples of every age solved the problem by using one chair and one lap rather than two chairs. Park benches are another great spot.

The bridges over the Seine provide another interesting contrast. On the bridges near Notre Dame, you frequently see couples embracing, but, generally speaking, they are tourists. They stop in the middle of the bridge, look at Notre Dame, and ta-dah, une grosse bise (a big kiss). There are so many couples doing it that it reminds me of late Saturday night / early Sunday morning in front of women’s dormitories back when there were curfews and no co-ed dorms. If the couple are wearing running shoes, Bermuda shorts, and carrying a fanny pack and a camera, they are definitely tourists. No Parisian would dress like that nor attempt an embrace where anything other than clothing is going to come between the embracer and the embraced. However, if you walk along the quais under the bridges, you find Parisians embracing and if you go for a nighttime ride in the bateaux mouches, when you pass under the bridges, Well!!!!

Since romance (or kissing anyway) is everywhere, all the time, why make a special holiday out of Valentine’s Day? Valentine’s Day is the American term. Le Saint Valentin is the French. If you look at a French calendar, every day is a saint’s day unless it’s a Catholic religious holiday such as Christmas, Easter, or Assumption. In France, February 14th is Saint Valentin’s Day just as February 13th is Saint Beatrice’s Day. In the past, there was nothing special about it. The idea of making a holiday out of something that over here is as common as the air we breathe (and a lot cleaner) came from America the same way that le Halloween became a holiday. If you want to assign blame for the globalization of American holidays, blame it on television and the movies. The French still do not celebrate Thanksgiving, the 4th of July or opening day of the baseball season. But think about it. There you are watching an American film dubbed in French on French television and there’s the American couple celebrating Valentine’s Day. How nice. And if it’s an American custom, it starts out with a good chance of being popular in France because of the average French person’s admiration for most things American. What the French laugh at in America is the American habit of using the word “French” for things that either the French don’t have or think of differently. You never see French Vanilla, French Toast (le pain perdu – “lost bread,”, a dessert and not for breakfast) or French dressing in France. French fries are pommes frites (fried potatoes).

An American custom achieves visibility and then business takes over. In the US, it’s a great day for greeting card manufacturers, candy makers, and restaurants. It’s almost the same in France. So, how do the French celebrate? If you’re already near the top of the Richter scale of romance, you need to think of something special. This is France, so naturally the first thing you think of is food. Restaurants plan special menus featuring all those foods that are supposed to make you feel and act the way actors do in the great romance movies. This is one of the holidays when, if you want to reserve a table in a favorite restaurant, you’d better do it weeks in advance. And then, of course, there are the chocolates. One of the chocolate specialties at this time of year is the heart-shaped bonbonier: a chocolate container filled with chocolates. And of course, let us not forget Champagne.

One aspect of Valentine’s Day that I remember from my childhood that you don’t have here is the Valentine’s Day celebration at school. I remember writing Valentine’s Day cards for all my classmates and putting them in a huge box. They would do the same. Right before the end of the school day, we would stop work, distribute the Valentines, and eat little heart-shaped candies that tasted like Necco wafers because they were made by the same company. School is very serious here. You don’t go to school to celebrate anything. You go to school to study – to work. It is also likely that your parents would not encourage you to give Valentines to your classmates because even at a young age you consider them competitors for entry into the best colleges and entry into the best colleges is based on exam results.

Valentine’s Day here seems to be just one more reason to have a good time, and “Vive la France,” they’ll never run out of reasons for having a good time.

Blog Post: January 9, 2025

I’ve been spending more time at home lately as I’ve been readjusting to life after major surgery. Given all the things I wanted to do, but couldn’t, I’ve had more time to read, think, and just look at the Internet. As someone who moved to a different country, I was interested in reading stories or advice from people who had had a similar experience. One of the things that stood out was the number of people wanting to give advice on social media platforms. The advice usually took the form of “Five Things You Should Do (or Avoid) When Visiting or Moving to (Name a Place.) Note: the number wasn’t always five, but it was frequently enough that it made me wonder if it was chosen for people who count using their fingers. But reading the online posts left me thinking about the following question. As moving to a different country is not the same as visiting it as a tourist, what do you need to do differently for planning and for actually living there? Also why do all the people giving advice online think they know what advice people want, but I’ll leave that for another day?

When you move, there are the major items that you’ll no doubt think of such as finding a place to live, creating a bank account, and getting a driver’s license if you need one. But when you’re there, there will also be the small things that occur as surprises, both pleasant and unpleasant. One thing you need to think about in moving that you don’t need to think about as a tourist is how are you going to fit in this new country. A tourist returning home after two weeks doesn’t need to. Here are some examples of different behaviors from France that you probably wouldn’t know unless you had actually lived here for a while. In France, when you speak to a sales clerk, before saying what you want, you need to exchange, “Bonjours” Bonjour means either good morning or good day depending on the time of day. Not saying it is considered disrespectful, but how would you know that? Another example: if a French person or family invites you to dinner at their home, it’s considered rude to arrive at the time they told you. You need to arrive 15 minutes later. You can bring a bouquet of flowers as a gift for your host, but you need to make sure there are no chrysanthemums in the bouquet. Chrysanthemums are only for graves. Assuming you speak French relatively well, you might want to participate in a conversation at the dinner table. But if you follow the American custom and wait for a break in the conversation, you’ll be waiting a long time because here everyone talks at the same time. People just interrupt each other.

If you’re planning on living in a country, how do you learn the do’s and don’ts? How do you fit in so that both you and the natives are comfortable? The obvious answer is that you learn by observing or by getting to know locals who not only will know the answers to questions that you might have, but will also be able to give you advice on something that never crossed your mind. There may be books on the subject, but customs change, and the books can be out of date.. I read a book about adjusting to life in France, but I was lucky enough to have family here so that I could check the accuracy of the book’s recommendations. I still remember the book’s recommendation that if you needed help arranging seating at a dinner party, the US Consulate could help you. That may be true, but I’ve never had to ask.

Once you’re settled and have learned the country’s language, you can start having discussions about things like work-life balance, or the appropriate role for government in providing health insurance.You may not always agree, but you will certainly have a better understanding of how the social system works in your new country, and you’ll be better able to form an opinion by comparing systems in two countries. It’s important to remember that you can’t plan for everything that might happen, but you can learn to notice with all your senses. You have to enter the country knowing that things will be different, but not knowing which things. There are those that you will find to be an improvement on what you knew in the US, and those where you’ll wish they did things as we do them in the US. In any case, it’s guaranteed to be an adventure: Enjoy it!

Blog Post: November 21, 2024

There are many things to see and do in Paris. Something you might not think of doing is looking at statues. You could easily spend more than a day looking at them. You find them in squares, decorating fountains, near churches, on bridges and sidewalks, and in parks. Unlike the day-to-day world of humans, the world of statues follows its own rules dictated by machismo, fantasy, patriotism, and political as well as intellectual certainties. As a result, the statues of women represent an appalling minority. The statues of “les grands hommes,” (great men) are to be found everywhere, and animals are used to enhance the greatness of these gentlemen.

But given their minority status in the realm of sculpture, let’s first look at what it takes for a woman to be celebrated. Apart from a few exceptions, women have a symbolic function in statues. They represent “la Patrie,” (a strange word meaning literally the “motherly fatherland,” the republic, an inspiring muse, or a comforting angel.

When a statue represents la Patrie, it is a really impressive, majestic, and athletic woman. The best example can be seen in the monument at the Place de la Nation: at the top of the monument is a proud, tall, beautiful, and massive woman (la Marianne) wearing the famous “bonnet phrygien,” symbolizing the republic. Her right breast is exposed for all to admire the generosity and fecundity of her nature.

There is no fooling around about that bare breast. Marianne is a loving mother feeding all her children, unlike that selfish and destructive monarchy that preceded her. Marianne is also barefoot: she is from the people and quite like them – simple, stable, and solid. Being barefoot gives her better balance as she stands on top of the globe.

Our planet rests on a carriage drawn by two lions. Four characters surround the carri age. At the back is a completely naked woman. We see her from behind. A garland of flowers and sheaves of wheat robe the front part of her body with proper modesty. She embodies agriculture. On the right side of the carriage is a muscular fellow with a hammer. Yes: agriculture and industry unite harmoniously for the benefit of French prosperity as is shown by the cherub-like child nesting in-between his formidable parents.

The fourth character is in front of the carriage. He looks proudly ahead, leading the lions with one hand and holding the republican torch that will enlighten the world in the other.

When women are not represented as la Patrie, the republic, or agriculture, they will be shown kneeling worshipfully at the feet of a male writer or poet, or at the feet of some politician who freed the French from exploitation or ignorance. These same politicians didn’t grant women the right to vote until after the Second World War, and didn’t allow married women to sign a contract until 1960. When the females are not kneeling worshipfully or gratefully, they stand behind the great man, either to comfort him from his fellow citizens ingratitude or to inspire him to create some literary masterpiece.

There are a few exceptions. The first is Joan of Arc. A statue of this famous heroine stands in front of the Saint Augustine church. The young maiden is on horseback, her sword drawn and pointing to the sky in a proud, manly, and dignified attitude. This is classical, but the really interesting part is the horse. Its tail hangs down and its gait suggests a gentle trot. When you get closer, you can’t tell whether the animal is a stallion, a mare, or a gelding. As a symbol of the virginal nature of its rider, its general appearance must display decency, modesty, and propriety.

Another, and really touching exception, is the statue of “La Grisette.” A grisette was a young, working-class girl, rather poor because she worked as a seamstress for very little money. One way of earning a little more money was by not being extremely virtuous. The poor girls were more to be pitied than blamed as they were ruthlessly exploited both by their employers and episodic lovers, who were more often than not wealthy, married men. I find the realistic representation of the sculpture touching, not only because it conveys the transience of youth and beauty, but also the fragility and vulnerability of that poor outcast.

Unlike the statues of women, the statues of men are to be found everywhere. They fall generally into three categories: kings, whose memory is still celebrated in spite of the revolution; 19th century artists and politicians; and World War II heroes.

In spite of the massive destruction of symbols of royalty by 18th century revolutionaries, Parisians can still admire their statues. The statues of Charlemagne and Louis XIV are particularly impressive. The trouble is that when you look at them, you may wonder whether they are here to commemorate the greatness of past sovereigns or to glorify French virility. Anyone looking at the statue of Charlemagne at Place de Notre Dame will ask themselves that question. Charlemagne was really a great, good and efficient emperor in medieval times. He also had tremendous physical energy and was an active womanizer. He certainly contributed personally to boosting France’s birth rate.

Before moving to France, I lived in the town of Shirley, MA, which was named for a colonial governor, William Shirley. Governor Shirley was a descendant of Charlemagne. If you have any doubts about Charlemagne’s virility, simply look at his horse. Unlike Joan of Arc, here you can see that Charlemagne sat atop a stallion – a good, healthy one.

No women accompany our 20th century warriors: Marechal Leclerc, General de Gaulle, and Sir Winston Churchill. They all stand alone. Churchill’s statue decorates the garden of le Petit Palais. His gruff, efficient, sensible nature has been well captured. He seems to be walking at a brisk pace (on a low pedestal) with a purposeful look on his face. The statue of de Gaulle is beside le Grand Palais (noblesse oblige). It is on a tall pedestal so that the General dominates his friend and ally, but does not look at him. No, he looks upwards toward some lofty ideal. The problem is that if the statue were alive, it would probably fall over as by some strange artistic aberration or optical illusion, the General appears to be walking with his legs crossed.

Hôtel de Ville (City Hall) – Paris (Image source: Pinterest)

Blog Post: November 14, 2024

One of the things I needed to do shortly after moving here was get a French driver’s license. I don’t own a car and don’t need one in Paris, but it’s necessary when traveling in the countryside. To get the license, I had to go to driver education school because if you don’t, then it becomes nearly impossible to get a date for the written test – 40 multiple part questions and you need to get 35 or more correct. I took classes in a driver’s ed school in my neighborhood. Because I already had a driver’s license, I was eligible to take a shorter course, but my application and paperwork had to be approved by the Paris police department. The relation between the French and paperwork is not at all like it is for Americans and paperwork for US local, state, or federal governments.

The school secretary compiled my dossier, which included photocopies of my passport, my Massachusetts driver’s license, five ID photos, the visa allowing me to live and work in France, plus the standard application.

One of the lines to complete on the application was my birthplace: city, state, country. Easy enough for me, it’s Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA. The Paris police returned the dossier to the school, noting that it was incomplete, even though it had all the paperwork demanded by the police. The problem was that American passports list your birthplace as state, country while the French form also requires naming the city. You would think that wouldn’t be a problem; after all, you fill out forms and sign them to say that everything is true to the best of your knowledge and belief. Except that’s not the way it works here. The school secretary explained that the form was incomplete because it didn’t contain the city of my birth. To which I replied, “But yes it does, look, right there, I wrote “Cambridge.” “ She looked at me as if I was visiting from another planet and said, “Monsieur, it’s not acceptable to just write that you were born in that city, you need proof. You need to add a translated copy of your birth certificate to your dossier.” I still had one because I had to use it to make my way through some other bureaucratic roadblock.